Use Cases for Chemical Structure Searches in IP

Chemical structure searches are routinely needed for various intellectual property (IP) objectives such as establishing patentability/novelty, mitigating risk through freedom to operate analyses, invalidity competing patents and protecting IP positions. One may also use a landscape study to determine white space and assess competitor trends. It’s also possible to combine landscape, whitespace or FTO searching for the purpose of R&D planning and investments. In any of these scenarios, a structure search can provide insight and information paramount to a company’s IP strategy, defense and protection, but what are the challenges, and how can you be sure that you are getting the right search results?

Chemical Structure Searching – The Problem: Finding that Needle in the IUPAC

We all know that patents can sometimes be written in mysterious ways. This is especially true when it comes to chemicals and pharmaceuticals. There are often hundreds of ways a patent practitioner can describe a novel compound or small molecule, such as:

- One of several naming conventions

- Trade names

- Generic names

- Lab codes

- CAS Registry numbers

- Claim a compound by its chemical structure

- or even claim a family of structures

Patent or non-patent literature (NPL) authors may name a compound based upon International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nomenclature, while other authors use names based upon the Chemical Abstracts rules for identifying compounds and small molecules. Some authors may use a non-standard methodology, and in these cases, the chemical name may be apparent to a chemist, but does not follow a formalized naming convention.

Patent or non-patent literature (NPL) authors may name a compound based upon International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nomenclature, while other authors use names based upon the Chemical Abstracts rules for identifying compounds and small molecules. Some authors may use a non-standard methodology, and in these cases, the chemical name may be apparent to a chemist, but does not follow a formalized naming convention.

Worse still, many chemical compounds cannot be found by full-text searching at all. For example, a PCT application can easily contain 500 to 1,000 compounds, but it may be the case that not one of these compounds has a chemical name provided. As a result, chemistry searching can feel a lot like searching for a needle in a haystack.

Only a structure search can locate these compounds.

In order to effectively search for chemicals and pharmaceuticals, one should follow a two-pronged approach: utilizing both key-terms and structure-based search queries.

What is structure searching?

A chemical structure search occurs when a chemical structure is used as a search query instead of keywords or text. Done properly, a patent researcher that has chemistry expertise will “draw” the molecule into one of a variety of search tools. Some common terms in chemical structure searching are:

- Target – this is the molecule of interest, in patents or literature; think “the thing I’m looking for”

- Query – this is the molecule drawn as drawn for searching (but can include broader compounds as defined)

- Hits – any time the query matches a target

- Markush – a representation of a chemical structure commonly used in patent claims, which represents a group of related compounds generally rather than depicting every detail/atom in the molecule

- Similarity – searches for molecules which are similar to the query structure, in terms of calculated molecular descriptors or “fingerprints” of structures

- Substructure searching – identifies elements embedded within larger structures, allowing the retrieval of substances which match a query with substitutions at open positions

There are various tools that can be used for chemical structure searching, and ways that structures can be drawn into those tools. More on that shortly.

Two Prongs of Chemical Structure Searching – More Costly and More Difficult than One, But Worth It

The biggest obstacles in chemistry searching have always been that structure-based searching is an art in and of itself, and searching chemical structures thoroughly can become expensive due to the commercial database vendor fees. You’ll want an expert chemical patent searcher using these tools, and you’ll want them to get it right on the first pass. It is critical to know what the options are in terms of structure searching so you and your patent searcher can decide which options are best for your particular project.

The rest of this article is designed to help give you an overview of various structure search types, so that you can have a better understanding of what your options are and what your chemical patent searcher may be proposing.

1. Open-Source Tools

Recent advances in publicly-available chemical structure searching tools allow end users to quickly locate patent and NPL information on many molecules. Some examples of open-source databases are:

-

-

- PubChem

- ChemSpider

- SureChEMBL

- WIPO Patentscope (Registration with WIPO is required to use the advanced tools option)

- PubChem

-

All of these provide free access to chemical data extracted from patent literature. In many cases, PubChem and ChemSpider can also locate non-patent literature. Moreover, certain chemical companies like Fisher Scientific and Sigma-Aldrich provide structure searching tools to search the chemicals they sell.

2. Commercial Tools – Stop Needles from Slipping Through the Open-Source Net

Although open-source databases are helpful for getting an overall indication of what may be found in the chemical literature, relying only on these tools can be misleading, and may even result in missing key patents and journal articles. A comprehensive chemical structure search will cover commercial databases such as:

-

-

- Chemical Abstracts (CAS)

- Reaxys/Beilstein

- Derwent World Patents Index

-

These commercial databases use sophisticated methods to curate chemical compounds from the literature, and employ extensive indexing and coding of chemical species. To comprehensively search these databases via structure queries, the chemical patent searcher should have a strong background in chemistry and have extensive training in using these databases.

A scientist may have access to SciFinder, an end-user tool for searching chemical information. However, since SciFinder is a “generalist” tool, the more advanced chemical structure databases have higher level structure search capabilities and more in-depth techniques available.

Another consideration for selecting databases is the content available, e.g. patent and/or non-patent literature, such as journals, reviews, dissertations; as well as country coverage. Most of the commercial databases do a good job of covering the important resources from major countries worldwide.

While commercial databases typically have significant fees for structure searches and require professional assistance to reliably locate chemical compounds, they still provide a cost-effective solution when compared to the cost of a missed patent or journal article. Such an oversight can easily cost orders of magnitude more than a commercial database search.

The Right Tool for the Specific Job

There are multiple types of structure searches, and each has a unique set of advantages and disadvantages. In this section, we briefly explore the methodology and results of an example structure search, targeting the drug Aspirin, and using the following types of chemical structure searches:

- Exact Structure

- Family Structure

- Closed Substructure (CSS)

- Open Substructure (SSS)

- Markush

- Similarity

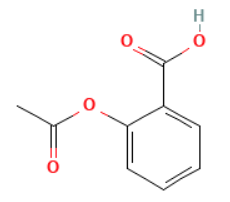

Type: Exact Structure

What it does: Retrieves only a specific compound or isotope.

When to use it: Typically used for novelty or Freedom-to-operate (FTO) purposes. Often the lowest cost option for commercial database searching.

Example Output: CAS Registry Number [50-78-2] Acetyl salicylic acid as an exact compound.

Type: Family Structure

What it does: Includes all of the exact hits and also includes salts and mixtures.

When to use it: Important when searching for pharmaceutical applications as many compounds also have salts such as hydrochlorides or hydrobromides. Other pharmaceutical compounds will have specifically defined CAS Registry Numbers on a mixture.

Example Output: CAS Registry Number [53908-20-6] Aspirin Mixture With Caffeine (unique entry in CAS files.)

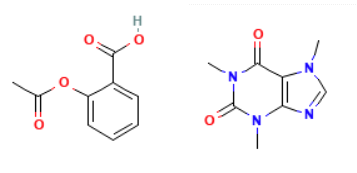

Type: Closed Substructure (CSS)

What it does: This search will allow substitution at defined positions, but all other sites are blocked. This will allow exploration of related compounds, but in a controlled manner. For example, a phenyl group was found whereby the original query defined a cycle (Cy) group at the left side methyl site.

When to use it: Useful for evaluating a precisely defined variability in a structure.

Example Output: CAS Registry Number [552-94-3] Disalicylic acid

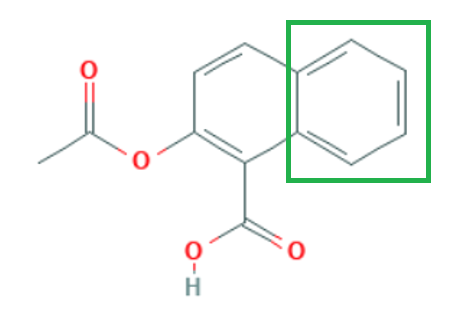

Type: Open Substructure (SSS) The CAS term is SubStructure Search

What it does: This is the most comprehensive search method as all sites are open to essentially any type of substitution. A key consideration is selection of additional ring fusion or ring blocking. If open ring fusion is allowed, the original structure query can be embedded into a more complex ring system. Typically, a full open structure search can locate more compounds than were originally anticipated.

When to use it: When maximum coverage of all possible structures is desired

Example Output: SCHEMBL1502327 2-Acetoxy-1-naphthoic acid (has ring fusion)

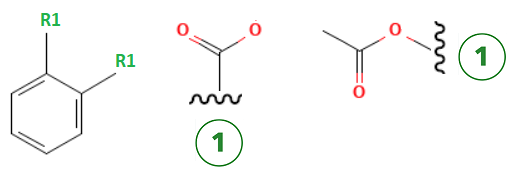

Type: Markush

What it does: This is an algorithm search method that attempts to locate whether a compound or broader species is covered by a genus claim. The output typically gives a “hit answer” set that shows how a compound may be covered by a broader genus. However, the end user is responsible to fully determine the relevancy and coverage within a genus claim.

When to use it: To determine if a specific structure is part of alternative species claimed in a patent

Example Output: A generic claim to the structure of aspirin

In Markush claims, the phenyl may also be denoted as “aryl” and thus, R1 – aryl – R1 may also be a relevant answer.

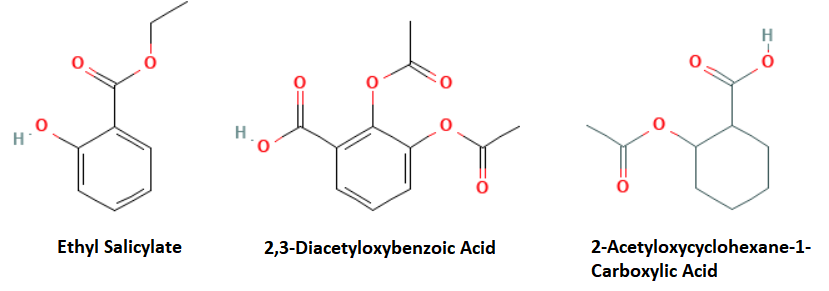

Type: Similarity

What it does: Also uses an algorithm to locate compounds that have a structural “likeness” to the original query. Unlike substructure searches, these are not limited to compounds that must have at least part of the original structure in a compound. Often returns answers that are considered complementary to the query, but locates compounds that have chemical motifs in common.

When to use it: To find alternative compounds that may be related to the original structure, but can fail to be located be a standard substructure or Markush search

Example Output: These hits are typically used to explore other possible related compounds that may be relevant to an invention. For example, the original Aspirin query contained an acetyl node and an aromatic phenyl ring. A similarity search may locate a compound having a saturated cyclohexane ring or multiple acetyl nodes.

Chemical Structure Searching – Conclusion

In combination, the above structure search methods are a powerful set of tools that can locate literature far beyond what any keyword or chemical name searching method can produce. To emphasize again: since Markush and Similarity methods are based upon algorithms, an experienced chemical patent searcher should know how to properly utilize these techniques as part of an overall structure search strategy – if this is not the case, important patents and literature are almost certainly not being captured.

In summary, chemical structure searching may not be inexpensive, but it does produce results that may be impossible to locate otherwise. The best search strategies for chemical structure searching include both commercial and open-source databases, followed by manual review from an experienced chemical search professional. This is the most cost-effective methodology to reduce IP risk while providing a high level of value for the client.

If you have questions on this topic or you would like to discuss a patent search project, please contact our experienced search team.

© Copyright 2023, Technology & Patent Research International, Inc.